The Witness of Thomas Merton’s Inner Work

by Jonathan Montaldo

Presented to the Parliament of World Religions

The 18th century Japanese hermit, Ryokan, wrote this poem:

“Book after book you may read to advance your knowledge, But I ask you to read just one word of truth.

What is the one word of truth for your reading?

To read your heart as it truly is.”

Every thing that is beautiful, true and good exists in order that all creation, the rock and the river, the lion and the lamb, and all manner of human beings might have life together and have life more abundantly. Our minds seek what is beautiful, true and good as naturally as we breathe the air of this room. No word from us is necessary to engineer their presence. Beauty, Truth and Goodness are as intimate to us as blood streaming through our veins.

God, it has been written truly, is as close to us at every moment as the carotid artery that laces our necks. God the most merciful and compassionate, God who is Emptiness, God Trinity, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, God the Messiah who is to come, God who is Holy Wisdom and Mother of us all, God beyond all our conceiving God clings to our minds as sinews of flesh cling to bone. Nothing can change God's presence or intention to love us. Our right relations to God and to one another are established. We need only be mindful of ourselves as we already are: God-fashioned, God-seeking, desired by God to desire God. "God loves us and espouses us as God's own flesh " [Thomas Merton. A Search for Solitude, Journals, Vol. 3, p. 70]. We who sit in this room are one body. We have only to awaken our minds and realize it.

The date is June 29, 1968. Thomas Merton, a monk of Our Lady of Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky in North America, French by birth who for a time carried a British passport until he became a citizen of the United States after being a Trappist monk for eleven years, is writing in his journal. He has spent almost twenty-seven years practicing a monastic discipline in the Christian tradition. He is six months away from his death by accidental electrocution in Bangkok, Thailand. To the world he is an icon of success, his opinion sought by social activists, fellow monks, poets and seekers within religious traditions east and west. He is an internationally read author translated into twenty-eight languages. But looking over his shoulder at what he writes in his journal, we read words of one who sorrows, one who is unsatisfied, one poor human being although famous who still yearns to transcend the too narrow image of God he has carved for himself.

Thomas Merton, after twenty-seven years of monastic discipline, was not yet the monk, nor the Christian, nor the human being he had idealized himself yearning to be in his autobiographical writing. At the top of a 10,000-foot pole of fame, Merton counted his golden reputation as dross in the face of his need for more inner work. He needed to "de-form" his hardened identities as monk, poet and social-commentator so as to reform his mind by imprinting it with the universal and fluid sufferings of all other creatures. He needed to identify his mind ever more deeply with the mind of his Christ, the Christ who humbled himself so that God could be conceived as the Most Accessible of Neighbors. Merton knew that his inner work was more important than anything he could teach or witness to others by mere words.

In his journal entry for June 29, 1968, he comments on his reading of the eighth-century Buddhist scholar Shantideva whose writing described the inner work necessary to become a Bodhisattva:

- "I am spending the

afternoon reading Shantideva, in the woods near [my]

hermitage-the oak grove to the southwest-a cool,

breezy spot on a hot afternoon. Thinking deeply

of Shantideva and my own need of discipline. What

a fool I have been, in the literal and biblical

sense of the word: thoughtless, impulsive, lazy,

self-interested yet alien to myself, untrue to

myself, following the most stupid fantasies,

guided by the most idiotic emotions and needs.

Yes [being human] I know, it is partly

unavoidable. But I know too that in spite of all

contradictions there is a center and a strength

to which I always have access if I really desire

it. The grace to desire it is surely there.

"It would do no good to anyone if I just went around talking-no matter how articulately-in this condition. There is still so much to learn, so much deepening to be done, so much to surrender. My real business is something far different from simply giving out words and ideas and "doing things"-even to help others. The best thing I can give to others is to liberate myself from the common delusions and be, for myself and for [others], free. Then grace can work in and through me for everyone.

"What impresses me most-reading Shantideva-is not only the emphasis on solitude but [his] idea of solitude as part of the clarification [necessary for] living for others: [the] dissolution of the self in "belonging to everyone" and regarding everyone's suffering as one's own. This is really incomprehensible unless one shares something of the deep, existential Buddhist concept of suffering as bound up with the arbitrary formation of an illusory ego-self. To be "homeless" is to abandon one's attachment to a particular ego-and yet to care for one's own life (in the highest sense) in the service of others. A deep and beautiful idea [in Shantideva when he writes:]

"'Be jealous of your self and afraid when you see your self is at ease and your sister is in distress, that your self is in high estate and your sister is brought low, that you are at rest and your sister labors. Make your self lose its pleasures and bear the sorrow of your fellow human beings.

[The End of the Journey. Journals Vol. 8., pp. 135]'"

Shantideva's words reminded

Merton again that his years of monastic discipline were

only preparation to receive the grace that would cut the

knot of his ego's distorting conceptions and free him to

identify his true self with the selves of all who suffer.

In his journal writing especially Merton discloses the

nature of his inner work as he confesses his evasions of

the task to efface himself in deeper communion with the

anxiety of his fellow beings. Thomas Merton is a

spiritual teacher whose words will benefit new

generations in the 21st century because he never lost the

docility of a student who knows by deep experience that

he is not wise. Seeking God, Merton continually displaced

his mind on a journey to deeper mind and to a deeper

communion with all that is true, good and beautiful: the

enfleshment of God in all things.

Thomas Merton's memoirs made him famous. The Seven Storey

Mountain, the narrative of his journey from a homeless

prodigal to one who found his nest at a Trappist

monastery in Kentucky, remains in print today since 1948.

In the twenty years that followed this best-seller until

his death in 1968, Merton wrote volumes of poetry,

popular books on the spiritual life, and hundreds of

essays engaging his wide, passionate interests:

contemplative traditions East and West, world literature,

politics and culture, social justice and world peace. His

magazine articles fill fifteen large volumes. His

collected letters to the famous and to just plain folks

nears ten thousand items. Seventy working notebooks on

his reading prove he studied as carefully as he wrote.

Six hundred audio taped conferences to his monastic

novices highlight his gifts as a teacher. Among all these

things and more that are archived at the Thomas Merton

Center at Bellarmine College in Kentucky most revelatory

of Merton's gift for communication are his private

journals. Twenty-nine years of personal journals exist

from 1939, when Merton was fresh from Columbia University

in New York City until just two days before his death.

These journals are, in his own words, his art "of

confession and witness." They are his testaments of

a poet's "heart work," of a scholar's "inner

work, of a monk's "work of the cell." His

journals provide a window for its reader to view, over

his shoulder, the necessary struggle of us all to

transform our consciousness from self concern with

securing ourselves in the world to selfless

identification with all that is fragile and transitory.

Merton's journal writing and its lessons fall within the

genre of monastic wisdom literature. Unless we change our

hearts and become new beings by inner work, our outer

work with and for others in community contributes only to

prolonging the endless cycles of bondage and despair.

Without the continuing inner work of exorcising the

distorting conceptions of an isolated, private self, the

community's distorting conceptions of itself can never be

exorcised. Institutions cannot be changed unless we who

create and maintain institutions are transformed. Our

lofty calls to guiding institutions [the core document of

the World Parliament in South Africa] are authentic only

as we commence and sustain the conversion of our own

misguided hearts.

It is true that Merton publicly called upon institutions

within the West, and especially within his own North

American culture, to renovate themselves according to the

social principles embedded in the Judeo-Christian

scriptures. But his monastic tradition and his own

experience taught him that his calling upon institutions

to reform themselves would only be heard if it came from

one who was attempting to reform himself. The teacher who

is not first humbled and judged by his own words of

instruction to his society is a false pedagogue and

rightly ignored. The transformation of his own

consciousness had to proceed in tandem with his call for

a transformation of institutional structures.

He

explained the dynamic balance between inner and outer

work in a published journal, Conjectures of A Guilty

Bystander:

- "Since I am a [human

being], my destiny depends on my human behavior:

that is to say, upon my decisions. I must first

of all appreciate this fact, and weigh the risks

and difficulties it entails. I must, therefore,

know myself, and know both the good and the evil

that are in me. It will not do to know only one

and not the other: only the good, or only the

evil. I must then be able to love the life God

has given me, living it fully and fruitfully, and

making good use even of the evil that is in [the

life God has given me]. Why should I love an

ideal good in such a way that my life becomes

more deeply embedded in misery and evil?

"To live well myself is my first and essential contribution to the well being of all mankind and to the fulfillment of [humanity's] collective destiny. If I do not live happily myself how can I help anyone else to be happy, or free, or wise? . . .

"To live well myself means for me to know and appreciate something of the secret, the mystery in myself: that which is incommunicable, which is at once myself and not myself, at once in me and above me. From this sanctuary [of the mystery in myself], I must seek humbly and patiently to ward off the intrusions of violence and self-assertion. . . . .

"If I can understand something of myself and something of others, I can begin to share the work of building the foundations for spiritual unity. But first we must work together at dissipating the more absurd fictions that make unity impossible

[Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, pp. 81-82]."

The work of building the

foundations of spiritual unity, according to Merton,

begins by piercing through the fictions that attend our

lives and work. The fiction, for example, that we who

attend this Parliament must dissipate is that this

gathering constitutes in fact a parliament of our

religions. Religions do not congregate in parliaments,

persons do.

We owe it to reality for each of us to pierce

the corporate veil of this Parliament and remind

ourselves that, behind every formal declaration are our

human faces, behind every institutional mask is an

awkward coalescing of us struggling for coherence and

meaning. Our formal, strategic plans are abstractions of

our anxious desires for harmony out of chaos. Behind

every rigid dogma we corporately create is a chorus line

of us the lame that only wants to dance.

Our kind, our

poor human kind on no matter what continent, no matter

living in a village nor a metropolis, dearly loves the

fictions and the cages we construct, not only to protect

us from the strangers beyond our borders but from the

unacknowledged resident aliens within our own hearts.

The significance of

Merton's inner work for our learning was his life-long

effort to uncage his mind. Grounded in his Christianity

and naturally unable to abandon his deep roots in Christ,

Merton uncaged his mind with Christ to push outward

toward a more catholic light by studying contemplative

traditions of the Far and Middle East. He uncaged his

mind by the practice of desiring to learn from all

expressions of God-seeking. Merton's inner work freed him

from any one-source theories of what it means to love God

and serve one's neighbor. By study, by prayer, by

solitude and by writing journals Merton softened his

heart and made himself pliable for the grace that would

free him from self-delusions so as to be more free for

others. He summed up the essence of this inner work in

his journal:

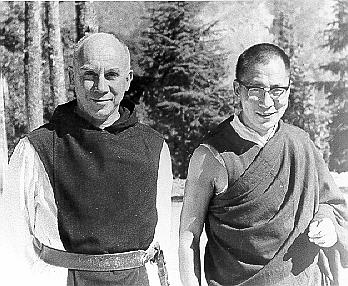

Thomas Merton and His Holiness the XIVth

Dalai Lama (India, 1968)

- "If I can unite in

myself, in my own spiritual life, the thought of

the East and the West, of the Greek and Latin

Fathers, I will create in myself a reunion of the

divided Church, and from that unity in myself can

come the exterior and visible unity of the Church.

For, if we want to bring together East and West,

we cannot do it by imposing one upon the other.

We must contain both in ourselves and transcend

them both in Christ

[A Search for Solitude. Journals, Vol. 3, p. 87].

"This European born and educated monk strove to uncage his mind from the distorted perspectives of a western, mono-cultural approach to human realties and relations. Merton's inner work could be characterized almost wholly by the desire to free himself and help others free themselves from the distortions of their education, their national heritage, their tribe, any entity that divides human persons into family and strangers. Deeply embedded himself in a total institution where monastic rules, constitutions and an abbot directed every aspect of its members lives, Merton rejected anything that denied any person's inviolate freedom even in God's name. He believed that the first, legitimate duty of every institution was to contribute to the personal freedom of every human being. Freedom, for Thomas Merton, was inseparable from religion. True religion, he wrote, nurtured

- "Freedom from

domination, freedom to live one's own spiritual

life, freedom to seek the highest truth,

unabashed by any human pressure or any collective

demand, the ability to say one's own "yes"

and one's own "no" and not merely to

echo the "yes" and the "no"

of state, party, corporation, army or system.

This is inseparable from authentic religion. It

is one of the deepest and most fundamental needs

of [the human person], perhaps the deepest and

most crucial need of the human person as such….

The frustration of this deep need [for freedom]

by irreligion, by secular and political pseudo-religions,

by the mystiques and superstitions of

totalitarianism, have made [us] morally sick in

the very depths of [our] being. They have wounded

and corrupted [our] freedom, they filled [our]

love with rottenness, decayed it into hatred.

They have made man a machine geared for his own

destruction

[Conjectures of A Guilty Bystander, p. 77]."

Thomas Merton has been called a

"spiritual master" and publishers of his books

claim that he was one of the twentieth century's most

significant theologians. He was indeed a gifted writer

and teacher whose wide-ranging evocation of what it feels

like to lead an examined inner life marked by intense

prayer rightly attracts all those who seriously seek God.

But Merton's great gift to his readers is that his

monastic discipline and inner work did not allow him to

confine the contradictory parts of himself into leak-proof

compartments. He always acknowledged in his journals the

disturbing conceptions that attended his mind's religious

journey. His right hand always knew what his left hand

was doing. His genius for honesty in his journals and his

urge to make his contradictions more transparent reveal

to his reader how dark and hard is the long, graced road

to inner freedom. His transparency in his journals reveal

to his reader that his life was no metaphor for mastering

the Spirit but rather a paradigm of being mastered by the

Spirit as his ego slowly dissolved into identification

with the suffering of everyone else. Merton wrote

journals to undermine his guru status. He allowed the

honesty of his journals to convince him and his readers

that he was nobody's "answer," not even his own.

But Thomas Merton was no virtual monk. His was a literal

quest to find himself gathered by God's mercy, a mercy he

knew by hard experience he could never bequeath to

himself. He literally sought to live for "God Alone."

He literally desired to find himself hidden in the "secret

of God's face." Merton's tears and his expressions

of sorrow in his journal writing would have been

pathological had they not proceeded from his literal

desire to obey God's voice and go, as he put it,

- "clear out of the

midst of all that is transitory and inconclusive

[and return] to the Immense, the Primordial, the

Unknown, to Him who loves, to the Silent, to the

Holy, to the Merciful, to Him Who is All

[Turning Toward the World, Journals, Vol. 4, p. 101]."

Merton was, like every one of

us, a complex human being. The mystery of his inner

complexity, the diverse expressions of his person as he

responded to the world and its ten thousand things were

as puzzling to him as the mystery of our own inner

complexity makes each of us puzzles to ourselves. Like us

he imagined that achieving unity of experience and

clarity of self-expression would be metaphors for

entering the presence of God. But he was so multi-faceted

a person that a consistent, clear expression of himself

to himself escaped him. He was always a stranger to

himself, full of new and paradoxical possibilities.

When

Merton corresponded with his closest friends in letters,

where he could be most heard and be most himself, he

hinted at this inner diversity by playfully signing his

letters with different names. He signed his letters

variously as: Roosevelt, Homer, Wang, Demosthenes, Joey

the Chocolate King, Ottaviani, Henry Clay, Harpo,

Cassidy, Moon Mullins, and Frisco Jack [see The Man in

The Sycamore Tree by Ed Rice and A Catch of Anti-Letters

by Merton and Robert Lax]. His two most significant

names, his name in religion, Father Louis, and his

writer's name, Thomas Merton, were symptomatic of the

more deeply divided self-presentations of who he was.

Early in his monastic life he believed that the writer

Thomas Merton had to die if Father Louis the monk was to

live.

He had, just as you and I have, a chorus of

expressions of himself, some harmonious, some discordant,

and he wondered how all of these expressions could be him.

He consciously questioned which of all these names and

expressions of himself were true and which were false.

Which of his many self-presentations were his "true

self?"

Casting the dilemma within Merton's Christ-consciousness,

did God the Father love only a single expression of his

personality? Did the Father demand a paring down of

Merton's personality into a monochromatic purity? Or was

the Father's love for him as fecund and complex as the

fecund complexity of Merton's self-expressions? Did the

Father in fact love most these opposing energies of

identity that played themselves out in Merton's life and

art?

The great inner work to be accomplished in each

person's solitude and prayer is the acceptance of the

unaccepted contradictions at the ground of our self-presentations.

Inner work is a work of integrating these contradictions

so as to live with them and out of them as our way of

taking our part in the life given us by God. By inner

work we learn to rejoice in God's creativity and to

perceive the inner wholeness that binds all opposites.

Our religious traditions at their most authentic should

free us to find traces of God in all things. God loves

all manner of our being in the world and has made all

things in harmony. God wills us to recognize the hidden

consonance of all that is apparently opposed within

ourselves and within our societies.

As in our inner work,

so our communal work for justice and peace is futile if

we insist on the primacy of one form of being human over

another, of one religion over others, or by choosing a

mono-cultural path toward Joy for all beings that share

this planet. God loves our infinite diversity and has

choreographed an ordered dance of different stars.

The old and the new, the one and the many, the small and

the large: our gathering in South Africa is a metaphor

for this ballet of opposing energies that course through

all of us. We have come to South Africa not to merge but

to allow our polar energies to converge and simply dance.

We have come to Cape Town to place our minds and our

bodies proximate to one another, to be in close vicinity

to strangers not from our country, to strangers not

sharing our religious mind-set, to those outside of our

conditioned perspectives. Our physical togetherness in

Cape Town is indeed the triumph of our religious

imaginations. We are hoping, despite all our real

diversities, that we are dancing together on the waves

that push us toward the same shore.

We have spoken millions of words among ourselves during

these Cape Town days together but perhaps what has been

more important than our words and our seriousness and the

gravity of our solemn declarations has been our simply

being together in all our diversity and mystery. Merton

would conjecture that God loves less our words and loves

more the pauses, the silences between our words. Only

within the intervals of our silences, when we finally

have nothing left to say or can say no more, do our

hearts become attentive to the vocabulary of the one

language being spoken among us. Only in the humble

silences between our words can we recognize beyond all

words the common tongue of yearning for freedom that

unites us. In the pauses we will find the beat to which

God conducts the music of our Cape Town days. When our

surface minds speaking themselves endlessly finally go

silent in exhaustion, then the deeper reality of our

inner minds can forget their shyness, reveal themselves

and come out to dance.

In final paragraphs to his classic book, New Seeds of

Contemplation, Merton evoked the metaphor of our being

together and with God as "the general dance:"

- "What is serious to

human beings is often trivial in the sight of God.

What in God might appear to us as "play"

is perhaps what God takes most seriously. God

plays…in the garden of creation, and, if we

could let go of our obsessions with what we think

is the meaning of it all, we might be able to

hear God's call and follow God in God's

mysterious, cosmic dance. "We do not have to

go very far to catch echoes of that dancing. When

we are alone on a starlit night; when by chance

we see the migrating birds in autumn descending

on a grove of junipers to rest and eat; when we

see children in a moment when they are really

children; when we know love in our own hearts; or

when, like the Japanese poet Basho we hear an old

frog land in a quiet pond with a solitary splash---…the

awakening, the turning inside out of all values,

the "newness," the emptiness and the

purity of vision that makes themselves evident [at

such times], provide echoes of the cosmic dance.

"For the world and time are the dance of the Lord in emptiness. The silence of the spheres is the music of a wedding feast. The more we persist in misunderstanding the phenomena of life…the more we involve ourselves in sadness, absurdity and despair. But it does not matter, because no despair of ours can alter the reality of things, or stain the joy of the cosmic dance that is always there. Indeed, we are in the midst of it, and it is in the midst of us, for it beats in our very blood whether we want it to or not

[New Seeds of Contemplation, pp. 296-297].

Thomas Merton's inner work

helped him to rejoice in being a member of the human race

in which His God had become incarnate. His inner work

insured that the "sorrows and stupidities of the

human race" could never overwhelm him once he

realized "what we all are." His deepest inner

work made him inarticulate and full of awe and silent for

there was "no way of telling people that they are

all walking around shining like the sun [Conjectures of A

Guilty Bystander, pp.141-142]."

By the witness of his own inner work made manifest to us

in his private journals Thomas Merton encourages all of

us to write ourselves into the Book of Life by coming to

terms with our hearts just as they truly, mysteriously

are. Merton knew his personal dilemmas were universal. He

knew we all long to live our lives beyond the boundaries

of our parochial selves but that we fear the exhibition

of our infinite possibilities. He knew we all hide the

mystery of our heart's complexities not only from the

world but also from ourselves.

The common vocation to

which each of us is called is the inner work by which we

learn that at Life's banquet we eat the same food as

everyone else. We learn by inner work to take our place

at Life's infinitely long table and humbly receive the

sacrament of our life's particular moments. By inner work

we learn to time-share with everyone our universally

precarious human existence through which everyone falters

forward in alternating patterns of celebration and tears.

The inner work of each human heart can become a metaphor

of hope that nothing is God's poor, unloved creation. We

are called upon by inner work to share God's love for all

fragile and transitory creatures that mirror God's

infinite possibilities, to share God's love, that is, for

our fragile, transitory selves.

May Thomas Merton's art of confession and witness

continue to benefit humankind. May my interpretation of

his words this afternoon have done no harm. But let words

pale and let my tongue be silent before the quiet reality

of just how good, true and beautiful it has been to sit

together in this small room in South Africa with the

world and God in our bloodstream.

_______________

Jonathan Montaldo, director of the Thomas Merton Center

at Bellarmine University, delivered this address on December

7, 1999.

Parliament of World Religions at Cape Town, South Africa

All rights are reserved.